‘Are you question or answer?’

- Amanda Lear, Enigma (give a bit of mmh to me)

In 1978, Guy Hocquenghem, the father of queer theory, and camp disco diva Amanda Lear, called for an end to stable identities, genders and sexualities. Hocquenghem’s book Race d’Ep argued that coming out as gay was just another way to be narrowly defined and contained by society: a form of oppression in disguise as tolerance. The more upbeat Lear would sing about the seductive powers of becoming mysterious and opaque, in her camp hit ‘Enigma (give a bit of mmh to me)’. Her deep voice led to rumours that she had undergone gender reassignment, paid for by Salvador Dali no less. The song aptly appears on the soundtrack for Oisin Byrne’s film GLUE, which joins a number of recent queer memoirs – notably Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts and Juliet Jacques’ Trans (both 2015) – in grappling with how to represent someone who refuses to cohere into a single self. The subject in question is Byrne’s friend Gary Farrelly, an artist and performer playing an eponymous character. He won’t even admit to being human. Instead he insists: ‘I don’t think there’s one me ... I’m a federation of opinions’. And like a combination of Hocquenghem and Lear, he is half political thinker, half indulgent starlet.

By all standard measures the character Farrelly plays is hopeless: past 30 he has no job, no partner, no fixed abode. Yet it’s precisely such norms that he rejects. A mouthy misfit, he has developed an anti-state and anti-masculine philosophy to oppose a society which doesn’t accept him. ‘If utopia doesn’t exist outside of the body’, he proclaims ‘I sincerely hope you can construct one based on your own delusions, in your own mind’. Fantasy is chosen over reality. His solution for name calling and attempts to corral him into a more conventional life is to become elusive by following his changing whims and desires. He even refuses the fixity of a single gender for his multiple selves, appearing in mumsy dresses and pearl brooches, but with five o’clock shadow and male pronouns. Unconsciously echoing Hocquenghem, Farrelly argues that having just one name is a symptom of patriarchal ownership. Or as he puts it: names are handed out by the ‘Lord of the Penis Universe’, to which he retaliates by indifferently calling all straight men ‘Igor’.

But memoirs demand a singular subject, just as film conventionally requires continuity. Even stories of coming out or transitioning require a shift from only one self to another. Such conventions are at odds with queers who see identity as a muddier affair. Byrne’s response to this multivalent persona is a similarly hybrid mix of documentary, fantasy and pastiche. It’s a method that flags up the contrived nature of each genre – confessions are filmed in ornate settings, against chinoiserie wallpaper, indicating the theatricality of filmic truth. Farrelly certainly acts out an exaggerated version of himself. Yet a later scene imitating a dating profile wittily signals that all identity is a mixture of performance and confusion – ‘I like dirty weekends ... I like clean weekends’. This conflation of styles also shows the cracks in his carefully constructed delusions. At one point Amanda Lear’s ode to being a glamorous enigma ironically plays as Farrelly prosaically shaves his arse. It’s hard work to be your selves.

Indeed, GLUE obliquely refers to a difficult transition both in Farrelly’s life and that of the Ireland in which he grew up. He reveals that for years his judgment and ability for self-reflection have been impaired by the medication he was prescribed for his narcolepsy, making him extremely reckless. No longer taking those pills, he is for the first time encountering himself, considering his actions and working out who he might be. This comes at a time when Ireland – which only decriminalised homosexuality in 1993 – has popularly embraced LGBTQ rights and gender equality, with votes for gay marriage, against discrimination and legalising abortion. If queer culture has been shaped in response to condemnation – as Didier Eribon argues in his Insult and the Making of the Gay Self (1999) – social acceptance may leave many similarly wondering who they are and what their community might become.

At one point in GLUE, Farrelly meets a friend’s new born child – an encounter between an outsider and a subject who has a chance of full state recognition. Upon greeting the infant he notes the number of official tags she’s wearing and ambivalently christens her a ‘barcode baby’. Perhaps Farrelly is right to be suspicious of state recognition. Recent progress in sexual politics, such

as marriage equality, closely resemble the pseudo-tolerance Hocquenghem warned against: you’re free to be yourself, so long as you and your relationships look just like ours, and we can keep track of them. The question remains whether the cost of the freedom to be enigmatic or incoherent – the toll of being misunderstood, reckless, out of control – is one queers can bear.

Paul Clinton is a writer based in London. He is lecturer in curating at Goldsmiths, University of London.

08 Jul - 22 Sep, 2019

St Carthage Hall

GLUE, the first feature-length film by Irish artist Oisín Byrne, with artist and collaborator Gary Farrelly

Read morePublications

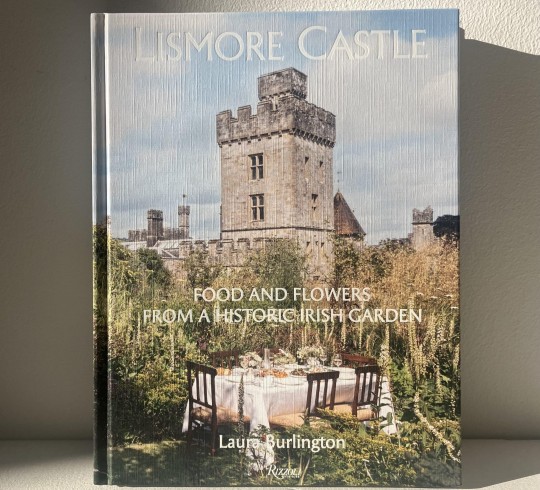

The catalogue to document the 2025 exhibition Kunstkammer, curated by Robert O'Byrne at Lismore Castle Arts.

Publications

Written by Laura and William Burlington, this book explores Lismore Castle's history and rich local food heritage

Publications

The exhibition catalogue to document the 2024 exhibition 'Each now, is the time, the space' at Lismore Castle Arts.

Publications

The catalogue to accompany Vertices, with work by Olga Balema and Anne Tallentire at Lismore Castle Arts: The Mill.

Publications

The catalogue to accompany Anne Collier’s exhibition EYE at Lismore Castle Arts.

Publications

Documenting the 'girls girls girls' exhibition curated by Simone Rocha, and designed by Eibhlin Doran.

Publications

Produced on the occasion of Michael Dean's exhibition Laughing for Crying

Publications

Featuring text by Polly Staple, curator of Still Life

Publications

Featuring texts by The Common Guild and Maria Fusco

Publications

Featuring an essay by Brian Dillon and interview with the artist

Publications

Featuring essays by Lisa Le Feuvre, Emily LaBarge and William T. Carson

Online projects/exhibitions

A series of conversations led by Deirdre O'Mahony drawing on her 'A Space for Lismore' commission, 2020

Lismore Castle Arts

Open Daily

Monday to Sunday

11am – 6pm (last entry 5pm)

13 March – 25 October 2026

St Carthage Hall

Fridays, Saturdays & Sundays

12pm – 5pm during exhibitions

Other times by appointment

The Mill

Fridays, Saturdays & Sundays

12pm – 5pm during exhibitions

Other times by appointment